The mighty oak

Ted Riddle shares his thoughts on oak and explains why, despite some faults, he rates it as the best timber in Australia.

I recently had the pleasure of touring parts of Western Europe with my family, and in passing, as I normally do; I took notice of the timbers. It seems I’m always looking for different applications.

Timber was the first great natural building resource and while you could make an argument for stone – particularly as you see the myriad buildings that adorn the cities, towns and villages of Europe – wood has been the easiest and most readily available building material over the last 5000 years or so.

In my time at the Timber Advisory Service I came across many samples of European Oak, mostly as furniture. Occasionally I’d see it as flooring, parquetry, panelling and the odd specialty moulding like picture frames, but nothing prepared me for the variety in which it is applied in Britain and Europe.

Quercus robur, or what Australians refer to as European oak, is actually English oak. Its native growth range is all across Europe into western Asia and is commonly the ‘oak’ of the country or region in which it occurs – think French oak for example – but basically its all the one species.

There’s approximately 600 Quercus species, all occurring naturally in the northern hemisphere with the two most notable being the Quercus robur and Quercus alba (the north American cousin of English oak known as American White oak). They are both very similar in colour, texture and figure and it would take a trained eye to tell them apart.

With so many other species in existence, it’s obvious that Q. robur is not the lone oak species in European forests but it dominate the flatlands and richer soil areas and as such is the major forest species.

It does co-exist with a species called Q. petraea which generally occurs at altitudes above 300m. In situations where they cross over, a hybrid species called Q. rosacea is created. The differences between the three species can be observed in the slight differences in the leaf shape or size and in the acorns (their reproductive seed or fruit). From a timber perspective the differences are almost impossible to pick. Certainly with the advent of DNA testing, species will be easily sorted.

In my many years in the Australian hardwood industry I felt we had the best hardwoods in the world. They are the strongest, hardest, most dense and durable and when you consider the ironbarks, tallowwood, grey gum and grey box, which we refer to as the ‘royal species’, timbers with lesser qualities seem to pale before them.

To my old thinking, English oak, which is much lower in density and strength (less than half the hardness or Janka rating) of these and many other Australian hardwoods like turpentine and spotted gum so it’s certainly not up there with our best.

In saying that though, just because a timber exhibits hardness and density, doesn’t necessarily make it better to work with.

One must also consider things like weight, drying ability and shrinkage. These can all have detrimental effects such as bad surface checking and end splits and being so dense can make timbers hard to process and work. If you have ever tried to nail, saw or plane ironbark after its dry, you will know what I mean.

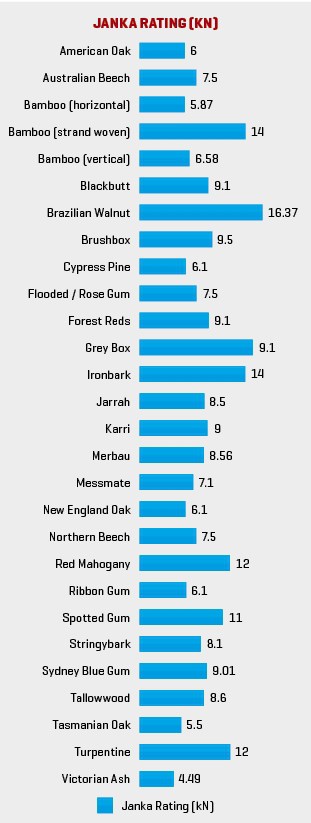

When asked about impact resistance and the Janka rating – used as the benchmark for flooring timbers – anything above 10 is considered excellent with anything below 7 considered low.

The species mentioned above rate 10-14 with species like blackbutt, red gum, jarrah and karri rating 8-10. English oak slots in at 5.5 and even our perennially durable softwood, Australian White cypress has a better rating at 6.5. So how could, in the eyes of a slightly biased Aussie, English oak, match with the best we have to offer?

As far as feature timber, I have always considered oak to be one of the best. It is great for furniture and joinery; it’s a pale yellowy brown with a distinct but course grain pattern featured by growth rings and the cross grain rays that provide a silvery appearance. It’s a very attractive timber. Despite oak being a bit slow to dry, with its shrinkage characteristics lower than most Australian hardwoods, it is easy to work and glues well.

I was certainly surprised at the extent and the range of usage in Europe, particularly for a timber of only medium durability and strength group 5 (where most of our hardwoods are 3, 2 and 1). It dominates many of the external and structural applications, especially in older structures and goes unnoticed because of weathering and discolouration.

A classic example of longevity include the posts, corbels and floor beams in the White Tower, the original building in the Tower of London, which dates back almost 1000 years. I think it is amazing that timber so old still does the job so remarkably well.

Until the mid 19th century all royal navy ships were built from oak, as were the viking longships a thousand years earlier; obviously a magnificent timber that can be turned to just about any task.

Wherever I looked from Edinburgh and Stirling Castles, in Scotland, where there is extensive use of flooring, much of which is worn and faded or the magnificent hammerbeam roofs in the great halls of both complexes, ‘green’ (unseasoned) oak featured heavily. With some structural maintenance caused mostly by shifting stone work, rather than fatigue or timber failure, has seen the timber stand the test of time for 500 or so years.

From the British Museum where there is some beautiful glass covered display cases, cabinets, shelving systems and tables to the darkened panelling, worn handrails and flooring of O’Neill’s Pub in Dublin, oak seems to be everywhere.

One of the great uses for oak is in the barrels for wine, whisky and beer. These days the major brewers are all changing to stainless steel but the boutique brewers still use oak and the wine makers of France, Spain and I guess the rest of Europe won’t use anything else. I am sure these beverages we enjoy wouldn’t taste the same if they did.

Who can forget the devastating fire at Windsor Castle in the early 1990’s, apart from substantial internal damage, the roof of the St. Georges Hall collapsed and to restore the structure they built a new hammerbeam ceiling. It’s the largest green-oak structure since medieval times. Along with many thousands of metres of panelling flooring and joinery, oak was the main species required for the heritage restoration.

Oak, like the softwoods of Europe, was severely overcut during the Industrial Revolution and used as fuel for the boilers to run the machines of progress; however, the development of silviculture and reforestation programs has seen English oak return as the dominant woodland species in Britain and Europe.

In many European countries oaks are used as symbols, often displayed on coins, notes, flags, coats of arms and of course the subject of the Royal Navy hymn ‘Heart of Oak’. Rather than just remain another species of timber or a tree in the forest, it seems to be part of the culture.

No other timber could be used for the building blocks of castles, bridges, wharfs and ships as well as homes, restaurants and pubs as well as lay the foundation for much of the floor we walk on, tables we sit at and chairs we sit on. Let’s not forget the barrels made from oak that age our favourite beers, whisky and wine…

I can’t think of a more dependable, versatile and reliable timber than English oak and in my time on the ABC radio show the ‘Homies’ I am often asked what I think is the best timber. In the past I have found it hard to qualify an answer but I think from now on I will easily be able to say the ‘Mighty Oak’; it’s hard to find an equal.