A little knowledge is a dangerous thing

As the VET landscape continues to change, most agree there is a place for both public and private providers in the sector. But glaring differences in the quality of training still exist between approved providers. Jacob Harris explains.

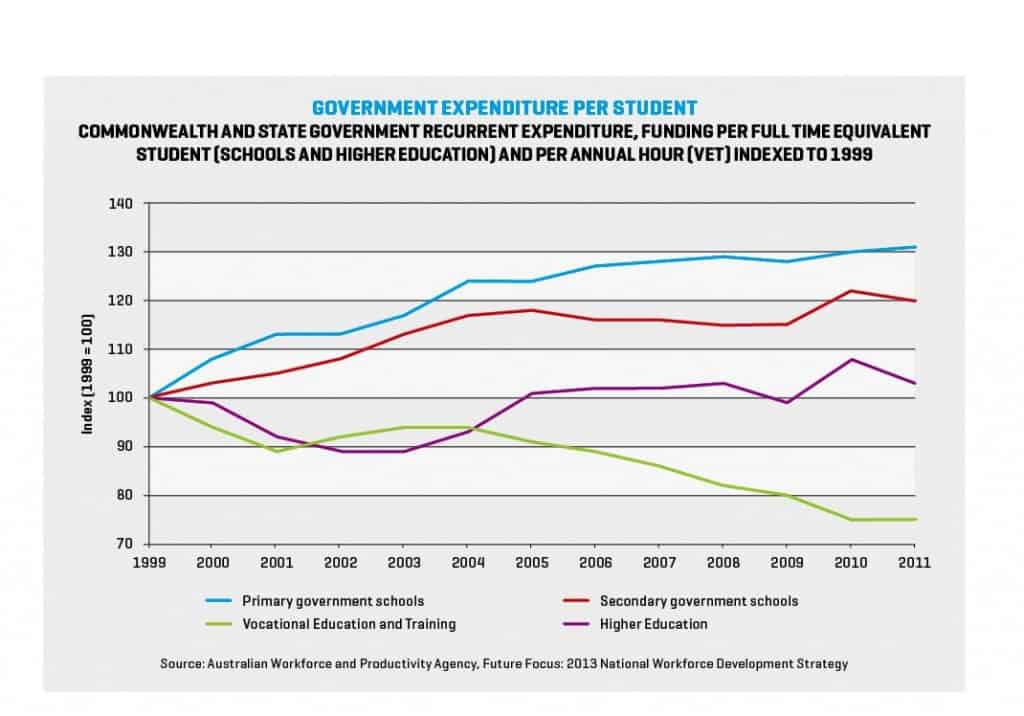

No one would dispute the value of a skilled workforce to a healthy economy but in recent times this sentiment has not been reflected in government funding to the VET sector. On a per student basis, VET funding has fallen dramatically while funding to government schools and (albeit to a lesser extent) higher education has continued to rise.

“Government funding is being squeezed and this is having an impact on the number of young people following a pathway into a construction trade. Apprenticeship commencements in construction trades are down some 20% since 2010,” CEO of Master Builders Australia Wilhelm Harnish says.

Entitlement based funding systems for the VET sector were introduced in Victoria in 2009, and subsequently in every other state. This made every student entitled to a subsidised training place with a public or private provider of their choice and led to a steep rise in the number of private RTOs in the sector.

The rationale behind the decision to make these reforms was that increased competition within the sector would improve the overall quality of training, with sub-standard providers being competed-out of the market.

When applied to commodities, increased competition can nearly always be seen as beneficial to the consumer as it drives down prices and provides more choice. But whether this same model can be applied effectively to education (or any other essential service) remains to be seen.

When applied to commodities, increased competition can nearly always be seen as beneficial to the consumer as it drives down prices and provides more choice. But whether this same model can be applied effectively to education (or any other essential service) remains to be seen.

Figures in the Australian Skills Quality Authority (ASQA) 2015 annual report released in October show 77% of RTOs failing their initial audit. However, ASQA’s Chief Commissioner Chris Robinson points out that, due to complex auditing procedures, the failure rate at the initial audit is not necessarily indicative of low quality across the board.

“There are now eight standards and some of those have 10 or 12 clauses so there are a lot of things an RTO has to abide by. It’s almost impossible for a large RTO to get a fully compliant audit – there’ll be something there they have to sort out. So the important figure is how many are compliant after they’ve had an opportunity to address anything that’s been raised and the answer to that is 87%. So it’s 33% compliant at initial audit, 87% compliant by the end of the audit process,” Chris says.

While the situation may not be as dire as the figures initially appear to indicate, there is near consensus within the industry that, even among the 87% of compliant training providers, there remains a marked disparity in quality of training being delivered. This begs the question, ‘Are standards too low?’

“The quality of training delivery is patchy across the country, with some TAFEs and private RTOs providing courses that meet the needs of employers far better than others. All RTOs use the national qualifications as a basis for their construction courses, but the industry is finding that there can be significant differences in the quality of learning that an apprentice has undertaken,” Wilhelm says.

“Take the unit of competency associated with the construction white card as an example. Some RTOs deliver a face-to-face, in-depth course over a whole day as an introduction to the industry before new entrants can go onto sites, while other RTOs offer a quick online course where students answer a series of basic multiple choice questions (where if you select a wrong answer you get another attempt until you get it right) all completed in less than 30 minutes. From the industry’s perspective, it is vital that the national vocational education regulator (ASQA) ensures consistency in learning outcomes from RTOs as we want our workforce to be safe.”

Surely disparities such as this – that see graduates of the same course, delivered by approved providers, ending up with vastly different skill sets – are indicative of systemic regulatory shortcomings that allow some operators to exploit students, and ultimately the industry, for financial gain.

Indeed, Chris Robinson agrees that greater consistency needs to be achieved and that many providers nowadays are offering courses that are far too short to be of any real value. And while he acknowledges that more work needs to be done in terms of policy, he also suggests that many of the inconsistencies are perpetuated by a general lack of public understanding when it comes to the requisite skillset of a given qualification.

“Often the consumers, employers and students, seek out courses that aren’t the best because they want something that’s cheaper and shorter. So I think there are some issues with consumers really demanding and driving quality from the RTOs as well. There is more work to do in policy terms and also by the industry to enable people to better identify what ‘quality’ is in VET. When someone is new to the sector and the only information out there is about how long the course takes and how much it costs, they’re not going to be able to make an educated decision,” Chris says.

While there may be consensus that disparities exist, how to remedy the situation – or even whether a remedy is needed – appears to be less clear. Gerard Healy is chief executive of Builders Academy Australia, an RTO that’s part of the Simonds Group, a business which includes volume builders Simonds Homes, that specialises in building and construction based courses. While Gerard agrees there is variance in quality between providers, he is not of the view that this is necessarily a negative.

“I think there is a lot of difference out there but that’s not necessarily a weakness of the industry. ASQA has done a lot of work in creating a higher bar in respect of the standards expected of providers,” says Gerard.

“There needs to be a firm stance from governments saying ‘this is what we want TAFE to do and this is what we want private providers to do’ because at the moment there isn’t necessarily clear guidance and I think that’s contributed to the issues currently facing the sector. We’re now in a contestable market, so we’re all competing and we’ve been able to be more flexible. Using our example, we’re opening up classrooms in different geographical locations with a variety of class schedules – so we’re providing a difference. I think when governments create that line in the sand we’ll have better clarity.”

To be sure, better clarity is needed. In an age when television programs like The Block, glamorise the idea of being a ‘tradie’ and push the message that construction is something anyone off the street can have a crack at by trial and error, quality of training is paramount.

While courses of questionable worth inmassage therapy, personal training and aged care abound, there is a danger that slick institutes with tick and flick assessment models will focus their attentions on the trades, targeting unwitting students who are looking to fast track their learning. The message that there are no shortcuts on apprenticeships needs to be universally understood. After all, these are skilled professions that require years of dedicated learning before proficiency can be achieved – and they don’t deserve to be undervalued.