Hardwood or softwood?

Generally speaking, wood is often put into one of two categories: hardwood and softwood. So how do you go about determining one from another and how are they characterised? Ted Riddle explains.

In all my years as a timber consultant, the most reoccurring questions surround hardwood and softwood. While the questions come from various people in different occupations, the questions are usually the same. ‘How do I tell the difference between hardwood and softwood?’ is a common one, as is, ‘What is the difference between hardwood and softwood?’

As a panellist on the Sydney ABC Saturday morning radio program The Homies, I often find myself fielding the same questions. The callers are predominantly punters from the general public who think one might be better than the other. And that is right, however one should not simply guess. It all comes down to which type is fit for the purpose.

WHERE THE DIFFERENCES LIE

It isn’t the difference between hardwood and softwood that makes it suitable for one job or another but instead, it’s the mechanical properties of each timber which will deem one species more appropriate than another. This includes the durability or its resistance to external factors such as insect attacks or the influence of certain chemicals.

The real variance between hardwoods and softwoods comes in the form of a botanical difference that in no way determines whether the wood is hard or soft. My understanding is that the terminology of hardwood and softwood goes back to early European times when the basic timbers used for building, fencing, joinery, tools, carvings and so forth were divided into the two groupings on the nature of their softness or easiness to work. This meant that species like the firs, pines and spruces were considered softwood while the ashes, elms and oaks were considered hardwood.

By the end of the middle ages, botany as a science started to flourish. With Europeans exploring the world and bringing back drawings, samples and specimens of so many new and exotic plants, there was a need for a better understanding of the variation between species, and groups of species, hence the beginning of the classification system used today. In saying that, from a timber perspective, the old terms of hardwood and softwood were never far from the common vernacular and so the confusion remains.

So, understanding that the hardness or softness of the wood has no bearing on the timber classification, I’ll explain where the difference stems from.

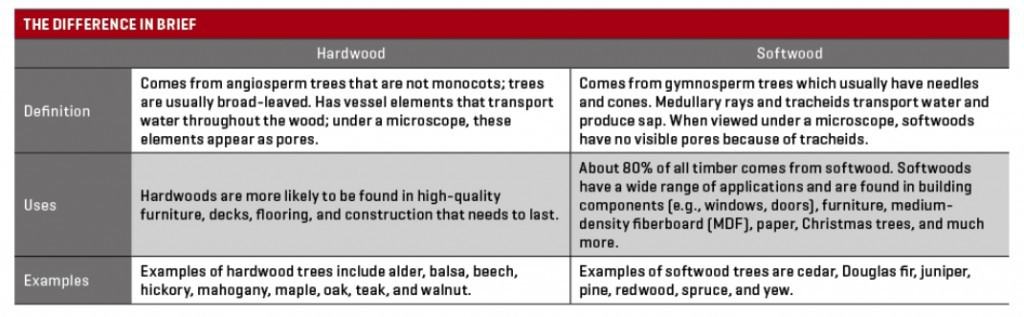

Hardwood comes from trees that flower, with the seeds for reproduction forming in a fruit, or, what some might call a nut. On the other hand, softwood comes from trees where the seeds grow in a very basic form at the end of the scales or leaves and usually clump into cones, hence the term conifers. That explanation provides you with a very basic understanding of the difference but doesn’t really help you to classify a piece of wood or timber upon sight. Again I am not sure that most people, regardless of their profession, really need to know, but most are curious.

INDIVIDUAL CHARACTERISTICS

Each group of trees grows differently; hardwoods come from the plants called Angiosperms and softwoods from those called Gymnosperms.

Gymnosperms are considered the oldest land plants, having developed 300-400 million years ago with early conifers appearing some 250 or so million years ago. Softwood trees as we understand them, with one exception, are all conifers and are basically made of woody cells called tracheids that run longitudinally up the tree. The tracheids themselves are not very long but they join together end to end to help form the trunk of the tree. Woody fibres hold the tracheids and other cells together and if you can imagine, it looks similar to a group of drinking straws bound tightly together with the fibre and other cells holding it all in a mass.

Angiosperms are the newcomers to the plant kingdom and evolved from the grasses that emerged less than 200 million years ago. Hardwood trees grow with large pores or vessels contained within the wood fibre and similarly link together end on end to allow the sap of the tree to move upward.

These growth characteristics provide the basic method for telling hardwoods from softwoods and somebody looking to determine if a piece of timber is a hardwood or a softwood can make a clean cut across the grain and then take a hand magnifying glass and examine the cross section. Softwood shows up just like the drinking straws, with all the tracheids lined up and bunched together very tightly.

Hardwoods on the other hand appear to be almost solid with the large pores dispersed seemingly randomly and in some cases visible without the magnifying glass. With many hardwoods the pattern and size of the pores can aid in determining the species of the timber, although it’s still a very complex task.

DETERMINING THE SPECIES

At this stage, being able to work out whether the piece of wood or timber is hardwood or softwood hasn’t really helped you to understand what species it is or if it’s suitable for the job you want it to perform.

You wouldn’t use a piece of balsa to stump a house, nor would you use a piece of river red gum to build a model aeroplane, particularly if you wanted it to fly. They are both hardwoods but we know where and how to use them from empirical usage, passed down over time with a wealth of experience. There are many trade and textbooks that offer us this information but they are not based on the difference between hardwood and softwood but rather on the individual species. This means that knowing the species is the most important factor.

The easiest and simplest way to determine the species is usually back on the forest floor in the way of foliage. Most commercial species have been documented (since the middle ages) to a point that by examination of the flowers, fruit, leaf structure, seeds, cones, bark branches, etc. the foresters can easily determine the species. So it’s fair to say that we rely on the skill of the foresters to know what is entering the timber market.

There is no doubt that a lot of species can be easily identified once they are processed but plenty of blurred lines make it difficult. Many pines for instance, look remarkably similar, but some have very different mechanical properties which determine whether or not they’re suitable for structural or external applications.

One of the most difficult things to do is accurately determine a species from a small sample. There are many wood technology options available that can measure and count the pore sizes in hardwoods, determine the density of the wood fibre, colour and the extractives from the lignin (the glue that binds it all together). There are also tests conducted on ash residue, where samples are burnt and tested scientifically; in many cases these methods can be definitive but they are time consuming and costly.

I recently wrote about the emergence of wood DNA testing in the fight against illegal logging, and I certainly believe it to be the future of species determination. With that being said, there are 600-odd softwood species and many thousands of hardwoods used as timber around the world. What is needed for DNA testing to become effective and available is a comprehensive bank of species control samples and the will or funding to do the basic research.

At present, there is a mapping program being developed to include many of the endangered and illegally logged species such as merbau and teak. My understanding is that 50 or so species have so far been identified. This is of course a large task because to determine if a species is illegally logged or from a protected area requires the developers to determine where the species being tested is from. That can be achieved with DNA testing but you have to test trees from all the growing areas to develop the map – easy enough to do but getting the sample and doing the testing requires a lot of work.

Developing the database of species DNA (without the regional locations needed in mapping) to provide what is referred to as the species fingerprint, is also fairly simple but is again a big task, because of the number of species, and at the moment there really doesn’t seem to be a commercial need. Perhaps it’s something that should be done on a country by country basis. That way each country can test their own commercial species and build them into an accessible digital database online; it seems practical enough but I can’t see it coming to fruition all that soon.