The challenges of multi residential thermal comfort ratings

David Arnott discusses the complexities that accompany a multi residential assessment when it comes to thermal comfort ratings. He emphasises that clear communication is the key.

The number of medium and high density residential developments continues to increase, particularly in our capital cities and populated urban areas. These developments are assessed in the same way as single dwellings, in the sense that each unit will have its heating and cooling loads measured through house energy rating software using the Nationwide House Energy Rating Scheme (NatHERS) protocols. However, there are additional complexities that accompany a multi residential assessment.

This article will explore some of these complexities, comment on what will influence a rating and provide advice on how to make the process as smooth as possible. Furthermore it will examine how the current requirements stack up when applied to multi residential developments versus single dwellings, and comment on the proposed draft changes to Section J of the 2016 National Construction Code (NCC).

It’s important to distinguish between a Class 2 and Class 3 building as they are assessed differently. Simply put, a Class 2 building is subject to the NatHERS method of assessment whereas a Class 3 building is not. A Class 3 building is assessed as a whole, in the same way an office building or retail area is assessed under Section J. This also means that in New South Wales, a Class 3 building is to be assessed under Section J and not BASIX.

Many little houses and not one big building

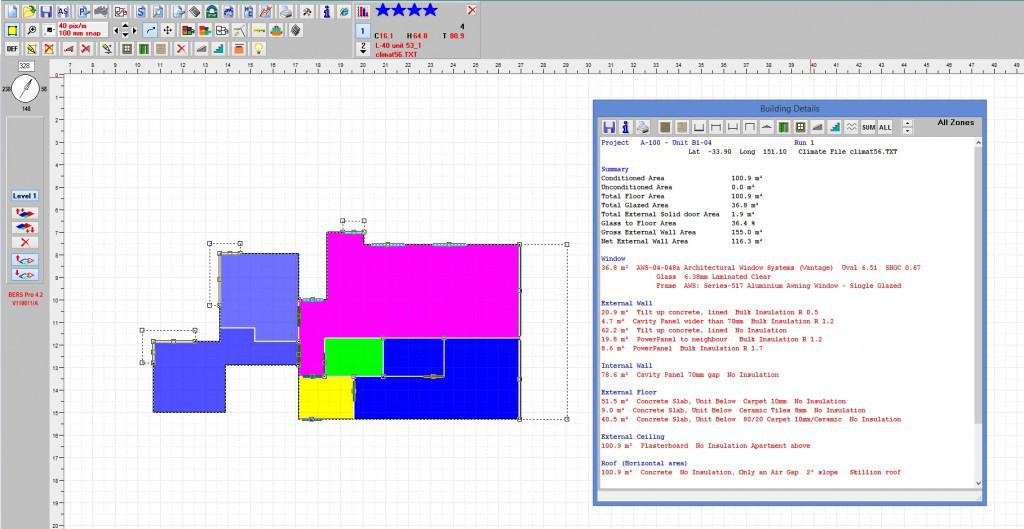

Thinking of a multi residential development as many little houses helps identify the scope of works involved in an assessment. If we consider a single home assessment, we know that we need the following details:

– The full details of the construction materials; i.e. structure, claddings, internal linings and insulation

– Either an individual window and door size schedule or clearly noted floor plans or elevations showing window type, operating type, window height, width and frame type

– Skylight and roof window details

– Ceiling and wall penetrations noted; most commonly penetrations from downlights and exhaust fans.

If we apply these requirements to a 300 unit proposal, to some degree we need the above information 300 times. Of course it is not this literal and there are some efficiencies. For example, it is likely that construction details will be mostly consistent, but on the flip side you also need to consider how these little houses are connected. Party wall construction is often different to external walls, which is different to internal walls.

This also means that 300 thermal comfort models are required for the assessment of a single proposal. Like the construction details, certain efficiencies can be made where a unit layout is duplicated, however these efficiencies may not be as great as you’d expect. The following are all items where a unit with the same layout will have a different performance:

– Roof, balcony or terrace above instead of another unit

– Open/enclosed subfloor below (including basement carparks) instead of another unit

– Change in orientation

– Unit layout mirrored

– The height above ground (this impacts wind speeds and potentially overshadowing)

– The same unit layout with different areas of glazing.

These two elaborations start to provide you with some understanding of the additional complexities. There is a high level of specific information required and significant time involved to complete assessments of this nature. Add this to the already multifaceted character of a multi residential proposal and the thermal comfort assessment can be exponentially more challenging.

If we compare these requirements to the requirements of a Class 3 assessment, where the building is assessed as a whole, hopefully a few things become apparent:

– The time involved in each assessment can be vastly different even where the proposed designs are exactly the same

– Internal changes in a Class 3 building are likely to have far less impact than internal changes to a Class 2 building.

‘There have been some minor changes but nothing that will impact your assessment’. This is a statement we regularly hear and more often than not, it’s wrong. This is not a criticism, but rather highlighting the fact that there is a general lack of understanding around what has an impact and what does not. I am confident the same statement would ring true for the myriad other consultants working on the same project; however due to the level of detail required and the protocol by which assessors must model, relatively innocuous alterations can have significant implications. There are two common types of alterations that fit into this category:

– Internal design changes that have no impact on the external appearance of the building, such as where the position of a living space and bedroom are swapped or where two single bedroom units are converted into one two bedroom apartment

– A change to a construction or glazing specification: on a whole of building assessment it would be rather minor to update but it is an entirely different exercise when you have to make that amendment 300 times.

Information overload

There have been recent changes to the NatHERS framework where an assessment is now issued with a universal certificate. This certificate contains all the required construction specifications associated with the assessment, with the aim of eliminating errors and improving built compliance. In a multi residential assessment every unit requires a separate certificate, therefore you have 300 certificates that will form part of your documentation. At five to six pages per certificate this is substantial. A summary of results is generated for Class 2 assessments; however, the level of detail in it does not include any information relating to construction. Therefore, in theory, at times, the certifying body will have to sift through hundreds of pages to confirm details and ensure compliance.

These new certificates also come at a cost. This varies a little depending on the software used, but most providers are currently charging $20 per certificate, so for 300 units that’s an additional cost of $6000. What is more significant about these fees is that you may need to pay them more than once. Every time the thermal comfort model requires an update the universal certificate will also be updated. As it currently stands, this means that the software will charge the $20 fee again. It is not at all uncommon for several revisions to be required over the life of a project so the impact of the new universal certificates could be rather significant.

Tips to make the process as smooth as possible

While the assessment process is more complex than a single home assessment and has its inherent challenges, it’s not all doom and gloom. Here are a few suggestions to help ensure a trouble free process:

Wait until your plans, matching elevation and sections are finalised before you ask your consultant to commence their assessment. This will help to avoid any required re-working which can add significant time to the job. If you want to get some preliminary feedback this is definitely achievable and it can be done by modelling a small selection of dwellings rather than the entire development. Keep in mind that this is only a guide; the results of this preliminary feedback may change if the design is altered. Even seemingly small changes can have large impacts.

Ask your assessor to give you an estimated turnaround time and plan accordingly. Understand that each dwelling needs to be modelled, which can require significant time investment. Quite often this fact is underestimated and when accompanied with the need for finalised plans this can put considerable strain on all parties involved with strict deadlines.

Communication is critical. Due to the complex nature of the assessment, there are more opportunities for oversights or mistakes, so keeping on top of the following is essential:

– Ensure all required specifications are on the plans at all times until construction is complete

– If anything changes, whether to the design or construction and specification, inform your assessor. They should be able to tell you if an update is required

– Address any changes as they occur. It becomes harder to update an assessment that has been constructed, but cannot gain its occupation certificate due to changes that have not been addressed.

– Further to this, you want to safeguard against any unnecessary revisions of the universal certificates by ensuring clear communication, so take the time to read and review items properly and clarify any ambiguities.

Given the additional complexities, is the current system appropriate?

In short, yes, but improvements could be made. No doubt the current system favours single dwelling assessments and the implications to large multi residential developments have been underestimated. It is not always appropriate for the same guidelines to apply to both single dwellings and multi residential proposals; it is an over simplification.

The universal certificates are a good example of this. They have been introduced with the aim of improving built compliance. It is easy to see how this can apply to a single dwelling; however, when the same method is directly applied to a 300 unit development it is likely to be far less effective. The aim will be lost in the reams of information, so a more considered approach would be more efficient.

The cost implication of the universal certificate might also be better considered when applied to multi residential projects. A reduced rate per unit would be a sensible start – similar to The Department of Planning fees charged for a BASIX certificate ($50 for a single dwelling opposed to $120 for the first three dwellings of a multi certificate and $20 for each dwelling thereafter). This coupled with the fact that fees need to be paid when a certificate is updated further adds to the burden of multi projects as they are updated far more often. This is particularly relevant when the assessment is required for a DA submission and some of the specific information required is not yet known. In this sense, instead of encouraging better built compliance it may actually discourage it because people are less likely to want to update a project when it incurs additional fees.

Alternatively, a whole of building assessment process, such as what is proposed in the draft National Construction Code (NCC), is not the solution. As has been largely documented this proposal is far too rudimentary and largely inadequate when compared with the current system. It would be a mistake to move backwards on the energy efficiency goals when we should be striving to improve.

A hybrid of the two approaches might be more suitable. A two tier approach could be more practical to the design, document, tender and construct process of a multi residential proposal. A preliminary whole building envelope assessment could be completed at DA stage. This would then be followed by a full assessment, where each unit is assessed, which would be completed at CC stage when all the relevant construction details are known. For this to be workable though, the preliminary assessment would need to be more comprehensive than what is currently proposed, to ensure compliance when the full assessment is completed. The current NCC deemed to satisfy provisions could be a good start.

If executed correctly a hybrid would improve the communication of specifications by minimising the time between assessment and construction. It could also reduce the additional costs that currently apply when updates are required. By doing so, it would encourage accurate assessments by ensuring what is modelled is consistent with what is constructed.

For the moment we need to work with the current system and if you take away one thing from this article it should be this: clear communication is critical.