All decked out and nowhere to go

In early October 2016 one of our corporate readers was referred to Ted Riddle, seeking advice, about a deck they had built about 18 months previous in a common area of their property. Here, Ted talks about best practice when it comes to specifying and installing timber decks.

Looking more like a walkway between buildings than an actual deck, the structure in question was performing very badly and the owners wanted to understand how they might be able to rectify the problems.

I didn’t get a chance to inspect the ‘deck’ and could only work from the couple of photographs provided (which unfortunately we could not publish) to highlight their thoughts about the problem and how they could be fixed.

The owners were under the impression they only had two options: either take up every second board and plane away a couple of millimetres from each edge and then re-lay the boards, or replace the entire deck. In my opinion, the only option was the latter. Even prior to looking at the photographs my first thought was that aesthetically, planing and re-laying each second board would look weird and certainly wouldn’t fix the other problem they were concerned about, and that was cupping.

It was fairly obvious from the photographs alone that there was no easy fix if they wanted the decking area to look good and perform well into the future. It was apparent that the original specifier had made allowance for the deck to be a commercial project but I don’t think using a 19mm decking board, which is really manufactured for a domestic application, was the best choice and probably not detailing the installation procedures left it up to common practice rather than best practice.

Regardless of the traffic on this deck, or what you could call a boardwalk, the application is certainly not domestic and I wouldn’t think it would have been acceptable in regard to the Building Code. I think the original specifier did get some things right though:

High durability timber species – Spotted gum. I was advised of this by the client and close inspection of the photographs indicated this could be correct – but very hard to determine.

Reduced joist spacing, therefore closer fixing points – judging by the screw fixing from the photographs, the spacings are somewhere around 300-400mm. This would certainly increase the load capacity of the Spotted gum decking.

Without a copy of the ‘Specification’ it’s hard to know if the spacing of the joists was an engineered detail or just an empirical understanding that in this class of building (non-domestic) the decking needed greater support given the higher than normal domestic loads it would have to sustain.

It is my understanding that a deck in this situation would probably be classified as ‘light pedestrian’ and should be designed to carry 4.5kN concentrated loads where all conventional load and span tables used for domestic decking are designed for 1.8kN concentrated loads; an engineer’s details would certainly be needed to approve the application of 19mm decking in this application.

Again, the specification would show if a coating regime had been included. Common practice is to coat the boards after being laid and after close examination of the photographs, it appears as though this was the case.

Best practice, and all timber industry recommendations is that all external decking, domestic or commercial, should be fully coated, that is both faces and both sides plus ends, with a water repellent or oil based primer before the boards are laid. This reduces the effect of weathering and decreases the absorption of moisture from humidity or rain and lessens the effect of cupping and expansion.

One of the problems highlighted when initially contacted by the client/owner was, in their idea, cupping and although the photographs indicate there is some occurrence, expansion of the boards due to moisture ingress seems to be more of an issue.

Coating all-round would have helped in both cases but two other elements play a big factor in the problems demonstrated in this project.

I am a great believer in the width to depth ratio of decking and I certainly advocate that the 3:1 rule should always apply. In a domestic application 60 x 19 hardwood (or closely thereabouts) and 60 x 22 treated pine meet the guideline suitably, once you go wider to say 88 or 90 mm the likelihood of cupping increases and if the boards aren’t coated all-round it further increases the chances. In this case a 25 or 30mm thick board would have been better suited.

Reducing the fixing spacing, which is bringing the joists closer together (what apparently happened in this project) and laying the concave face of the boards down, to the joist, may also help reduce the cupping effect.

The other factor involved here is decking spacing and according to the client the ‘specification’ called for 3mm between boards; I certainly believe that is too small a gap particularly for an 80-90mm hardwood decking board and the industry recommended spacing is 4mm.

If you coat the boards all-round this may be adequate as when you consider that high density hardwoods, such as those commonly used for decking like spotted gum, blackbutt, ironbark and tallowwood can shrink, in the drying/manufacturing process between 6-7% then there is a possibility they can expand that much when they take up soaking or atmospheric moisture when in place.

That is drawing the ‘long bow’ because it would mean the boards would have to be fully tangentially cut and that isn’t likely, but with back sawing being the preferred cutting method in New South Wales and Queensland (where all the high density, high durability hardwoods are produced) then there will be more tangential material than not and the expansion with prolonged high humidity or rain can be excessive, particularly in individual boards.

My feeling is 5mm should be the minimum spacing for a 100mm nominal size hardwood decking board and making a pro rate allowance, the wider the board.

Another issue is the quality of the boards being used. The ‘specification’ apparently called for spotted gum, to me a very good option, but I would like to know if it indicated a grade; the facial defects noticeable on some boards and the high preponderance of short lengths indicate to me that either a very low grade was purchased and the installer tried to cut out the defects or standards grade was used where the length factor is always shorter (because the manufacturer has done the same defect cutting exercise). In a high traffic, high aesthetic location, it certainly isn’t a suitable choice.

When faced with the problem of laying a deck with a high volume of short length boards (sometimes this might be unavoidable, depending on species, location, access etc.) taking the time to lay the concave face of the board down to the joist will help in minimising, not only the possibility of cupping, but also the mismatching of side peaking and end lipping; something also apparent in the photographs.

I have a photograph which I took (not from the same project) to show an example of the concave/convex end grain of a decking board. The two boards on the right would appear to be laid correctly, concave face down while the boards on the left, concave face up; I gather from that it was just luck of the draw, which would be the normal occurrence.

In this case it is work being done to restore a lifesavers lookout post on a Sydney beach, all the old treated pine decking has been replaced with kiln dried blackbutt, also a very good choice. The fixings are reasonably close together, about 400mm, the board spacing are at 4mm, but no coating all-round.

Another commercial application where work safety is paramount; it is only about a metre off the ground at the highest point (it sits near the crest of a rise on a sand dune, so good beach visibility). There is no real issue of safety from timber members giving way and people falling, even if it was only into the sand, but no coating of a walkway where council and volunteer lifesavers walk barefooted, should be a concern.

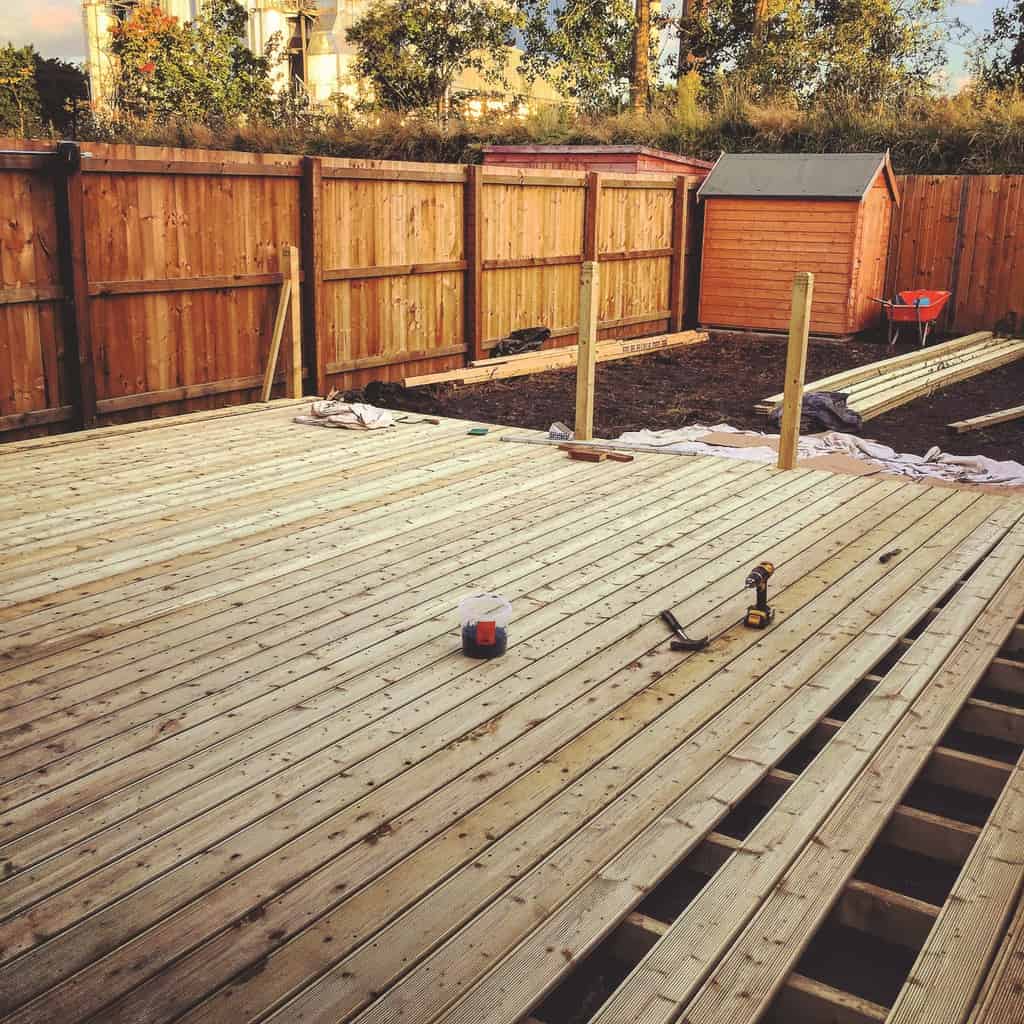

Carpenter installing new wood decking.

Blackbutt is a highly durable species, very good for external above ground applications, however it will expand and contract with moisture, and being near the beach where humidity and rain are regular occurrences, weathering will take its toll. As blackbutt weathers it tends to split and splinter, regular coating with an oil based waterproofing compound would keep it well preserved and much safer for the lifesavers and regular beachgoers who wander up and down to take a look at the beach.

To date, some 10 weeks after I took the photos, they still hadn’t been coated.

From the timbers’ perspective it might be a blessing in disguise, if the council were to now go ahead and coat only the top of the boards it would probably increase the likely hood of cupping. The coated face being the top, wouldn’t absorb as much moisture as the underneath; therefore, as the boards expand on the underside and try to stay stable on the face, the cupping will be more pronounced and any splitting more exaggerated as the process continues.

Both these examples highlight the difference between ‘common practice’ and ‘best practice’; common practice done for expediency, best practice avoided because of cost, the outcome in our first example is what is now the cost to remediate the deck/boardwalk and what will be the cost to council for a worker’s comp claim or a civil suit when some child drives a blackbutt splinter into their foot or leg.

Best practice makes sense in many ways.