Traditional trades still important to the building industry

Traditional trades still play an important role in Australia’s building industry despite a move towards mass production and the use of modern technology. However, a lack of heritage skills training is putting these trades, and the country’s heritage estate, at risk. Adelle King and Simeon Barut explain.

Over the past few years, there has been growing interest in heritage trades. In part, this is thanks to events like the Lost Trades Fair, which takes place in Kyneton, Victoria in March each year. However, the skills needed to keep these industries alive are disappearing and they are becoming something of a lost art.

There are fears that a lack of heritage skills training in Australia will impact on the conservation and maintenance of heritage icons.

As mentioned in the Spring 2017 edition of Building Connection, research released in 2016 by the National Centre for Vocational Education shows Australia is currently facing a national skills shortage in trades. Heritage trades, including carpentry, plastering and metal fabricating, are facing particularly tough skills shortages and have been included on the National Skills Needs List for years.

Despite these statistics there has been little done by the Australian government to ensure heritage skills are retained in the building industry.

“There is a distinct lack of heritage trades training in Australia, which is a real problem. Unfortunately the federal and state governments in Australia put very little money into heritage buildings and even less into heritage skills training,” says Centre for Heritage at Oatlands heritage manager Brad Williams.

The Centre for Heritage at Oatlands is an initiative of the Southern Midlands Council in Tasmania and was created to ensure traditional skills are applied and further developed. The Centre receives no government funding and is mainly funded through the Tasmanian Building and Construction Industry Training Board.

It aims to build the capacity of youth to undertake heritage conservation, restoration and maintenance projects, and provides education and training in all aspects of traditional heritage building skills.

“Heritage trades are niche markets but more people are starting to realise that they are also economic drivers that help fuel the building industry. We need more builders to become involved in heritage trades and more apprentices taking these trades on, but in order for that to happen there has to be training available,” says Brad.

“The market demand is there but trainers must work together with the government so that training is tied into legislation. There needs to be a formal requirement that contractors working on heritage sites require heritage trades training.”

The building industry has an important role to play in raising the profile of traditional trades and sponsoring training programs, workshops and events that provide young people with exposure to heritage trades.

Heritage and traditional trades can also be incorporated into modern building sites to improve end results and customer satisfaction.

In a survey of building contractors conducted by the Construction and Property Services Industry Skills Council, which advocates for national training and workforce development, more than 30% of respondents described current customer demand for work requiring specialist heritage trade skills as steady, 5.5% described it as healthy and only 17.8% described it as diminishing.

“The public seem genuinely fascinated by and respectful of heritage trades and the vast variety of skills and traditional tools employed,” says McMillan Heritage Plastering owner and director Scott McMillan.

Scott, who is a member of Australia International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) and the International Building Limes Forum, is originally from Scotland and spent much of his career working on projects on behalf of Historic Scotland. He was then approached to come to Australia to meet a demand for his specific skill set.

This is a familiar story for those working in traditional trades. The lack of heritage trades training in Australia means people skilled in traditional craftsmanship need to be sourced from overseas in order to meet Australia’s heritage conservation needs.

“There has been an increased awareness among those involved in historic building conservation that traditional skills are vitally important when carrying out repairs to heritage buildings. The correct training and skills ensure the longevity of conservation works, which honour the integrity of the existing building fabric,” says Scott.

“Unfortunately, the wrong techniques and inappropriate modern materials are all too frequently used for repairs on heritage buildings so moisture is sealed in, resulting in damage and decay.”

This is why companies such as McMillan Heritage Plastering, which specialise in heritage projects and use traditional materials, are so important. McMillan Heritage Plastering is one of the few traditional plastering companies that still adopt in-situ methods, providing expertise in traditional lime and ornamental plastering.

Traditional plastering uses putty lime as the main binder, which is breathable, soft in appearance and renowned for its unrivalled sustainability as a building material. Animal hair is often added into the mix to provide extra strength and to reduce shrinking and cracking.

While modern plasterwork focuses predominantly on mass production techniques, including fitting gyprock coving and applying bagged rendering products, traditional plasterwork involves specialised skills.

“Today, traditional plasterwork focuses on conservation and restoration work mainly for the care and repair of heritage buildings. Essentially, traditional plasterwork strives to match seamlessly into any existing heritage plaster elements. This is achieved through mastering a variety of intricate artisan handcraft skills to carefully execute a large scope of specialised ornamental works, including in-situ cornice restorations and decorative moulding reproductions,” says Scott.

Traditional lime plaster is applied directly to solid backings such as masonry or flexible supports such as timber laths in three coats, with a two-week curing time between each coat. Unlike the gypsum plaster used in modern building works, traditional plaster is breathable and flexible, allowing moisture to evaporate through the walls and ceilings to prevent damp and condensation.

“The high content of lime within traditional plaster allows the masonry substrate to breathe, which makes it perfectly suited for rising and falling damp treatments,” says Scott.

“Traditional plastering skills are therefore vital in the correct conservation of our shared built heritage. The time-honoured skills and expert workmanship employed in traditional plastering repair works demonstrate the utmost respect to the original building fabric. It also ensures issues such as moisture build-up, cracking and shrinkage do not threaten the building’s structure or aesthetic.”

In its 2017 State of the Industry Report, the Tasmanian Building and Construction Industry Training Board says it is concerned the building industry does not have the skills needed to be able to perform the conservation work required to maintain the state’s heritage sites. Previous research conducted by the Board found this problem isn’t restricted to Tasmania but is happening around the country, putting Australia’s heritage estates at risk.

“Inexperienced tradespeople employing the wrong techniques and modern materials can have a disastrous and irreversible impact on heritage buildings. Authentic and traditional skills safeguard the integrity of heritage buildings for generations to come,” says Scott.

However, it’s not just heritage sites that benefit from traditional trades. As an increasing number of customers turn away from cookie-cutter housing and towards customisation, traditional skills are also needed to help meet client specifications on new builds.

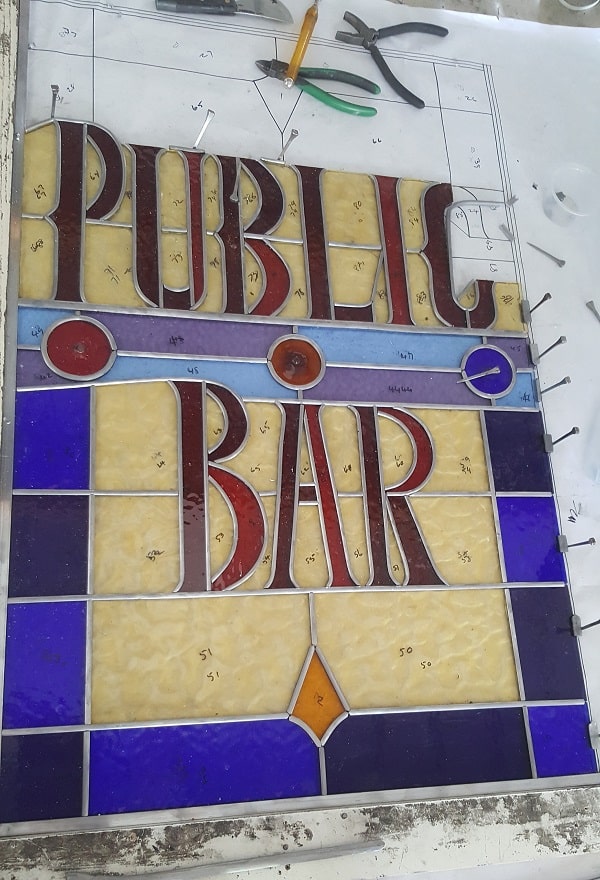

Most notably, leadlight windows are an increasing trend in new builds despite being most commonly known for use in historical structures and architecture.

According to Architectural Glass Design president Merinda Young, there are a lot of younger tradespeople wanting to incorporate vintage house decorations into contemporary house designs.

“There are a lot of people that do leadlight today that were part of the last resurgence 30 years ago and now that cycle is starting again with a lot of interest from young people,” says Merinda.

“Leadlight windows ties into the current interest there is in heritage architecture and while leadlight windows are a huge part of Australian history, it’s also something that can be amazingly contemporary. This is basically why leadlights are finding their way into new builds because they can be done in a way that fits a modern building.

“We’re also finding that the younger generation want more personality with their new builds and leadlights fit this perfectly. It’s a gross misconception that the design of a leadlight window still resembles something like your grandma’s curtains – it’s not like that at all. The design can be anything the person wants, which means they can implement a part of themselves with the final product.”

While leadlight windows are making their way into modern homes across the country, the production method hasn’t changed since its invention. According to Merinda, this is why it’s still loved by so many people.

“The design still has to be drawn up by hand to scale because every leadlight is different to the next one. The picture is then used as our template to which we cut the glass – the lead is stretched over the glass by hand, puttied, soldered and all cut manually.

“There have been attempts to change the technology but it has resulted in leadlights losing the unique element that makes them special. This is even more relevant now with the amount of new builds wanting a leadlight window that captures the modern and unique design of the house.”

The preservation method of leadlight windows also hasn’t changed since the 15th century as each individual window needs to be assessed. Leadlight studios currently put in place maintenance procedures that aim to prevent future failures of the glass. This involves using the exact same glass and lead that was used in the original production, which is then cut to size, leaded and soldered.

As with other heritage trades in Australia right now, extra effort is needed to help promote leadlight windows as a growing trade. Merinda says that this is often done through education and training but those in the industry already find it hard to offer this when there’s a lack of government funding.

“The most important thing is to help this trade grow is to continue to educate and train younger people who are showing an interest getting into the market. The sad thing is, a massive opportunity is being missed due to the lack of funding. There are so many people looking to get themselves apprenticed out into a reputable studio but we’re just not able to offer it without any funding,” says Miranda.

“Currently, as a body, we’re looking to form some training online but that won’t happen until there is some help from the government.”

Merinda believes the future looks bright for the leadlight industry but funding will be needed to ensure continuous interest from up-andcoming tradespeople.

“We continue to be in talks with institutions that are prepared to hold the training. There are so many young, talented and innovative people out there that do some remarkable things with leadlight so we want to nurture this talent so they can keep it going,” says Merinda.

A symbiotic relationship between permit authorities and heritage standards and training is important to strengthen the heritage trade uptake.

“There are so many people all around Australia working to try and address the heritage trades skills training but ultimately trainers need to be working closely with legislators otherwise nothing official will be put in place,” says Brad.

“I’m an optimist though. We have a lot of marketing force behind it so hopefully that eventuates into government awareness and additional funding.”