Preventing deck disease

Image 1: Functional failure tile debonded

A horrible, debilitating disease is gripping our country: drippy blisters, crusty growths, mouldy patches and rotten members are all signs and symptoms of this nasty condition. Home owners are the most affected, with the cost for cures running into tens of thousands of dollars – but builders can play a significant role in its prevention says Andrew Gollé.

The New Zealand Government has called this particular disease ‘Leaking Building Syndrome’ and have categorised any exposed waterproofed deck as being a high risk construction.

This disease, however, is completely preventable. Australian Standard 4654.2-2012 Waterproofing membranes for external above ground use is the referenced document in the National Construction Code (NCC) Volume 2, Part 3.8.1 and contains the technical Deemed-to-Satisfy building solutions required by the Building Code of Australia (BCA).

The NCC and AS 4654.2 are the mandatory minimum requirements to be followed in external deck design and construction. Too often, building practitioners treat these requirements as the maximum achievable and even try to avoid some mandatory steps and practices.

The omission of minimum step downs and sub-sill flashings, for example, breach these requirements and can result in the above symptoms, leading to functional failure and costly remediation.

Deck waterproofing components need to be viewed holistically and must incorporate a step down to outfall design. In other words, from door to drainage, it is imperative to marry these three key areas requiring detail:

- Step downs and vertical terminations.

- Deck treatment including penetrations and falls.

- Edge terminations and outfall details.

Defects: Types and causes

Deck defects can be categorised into two types. The first is functional failure, where the deck leaks and damage is caused to other building elements, or where the intended function of the building component deteriorates, such as debonded tiling.

The second type is classed as a cosmetic defect, where the deck is not necessarily leaking. These can be unsightly calcium and efflorescence deposits build up in grouting, or calcium line runs over the fascia. Other cosmetic defects may include compression of movement joints, blistering painted finishes or cracking grout joints (see Images 1 and 2).

Functional failures can result in rotted decks collapsing under normal loads, causing injury. During rectification of failed decks, we often encounter a number of faults, some of which only occur once another defect has appeared. A prime example is when dark coloured tiles debond from the membrane, allowing excess moisture to accumulate beneath the tiles. Areas beneath these tiles then turn into little pressure cookers when exposed to continuous heat cycles, which can stress and rupture membranes resulting in leaks.

Investigations often reveal numerous workmanship sins, where a number of defective practices or omissions have contributed to functional failures.

Door to drainage requirements

Door to drainage design needs to be considered holistically, as per the three key components mentioned earlier.

Wind driven rain at doorways is a common source of functional failure. Appendix Table A in the Australian Standard determines that vertical terminations, or tanking, are to be higher than doorway step downs (see Image 3). The table prescribes ranges from 34mm step down in N1 to 180mm tanking for N6/C4 wind rated areas. A majority of urban domestic construction occurs in N2/ N3 or C1 areas. N3/C1 requirements are for 50/70mm step down/tanking minimums. This is a good general practice benchmark. Any wind areas above N3/C1 should be addressed accordingly.

Under clause 2.8.3, where step downs are not possible, a gutter should be formed immediately in front of the opening. This typically takes the form of a grated drain connected to storm water. This design solution is useful for wheelchair access.

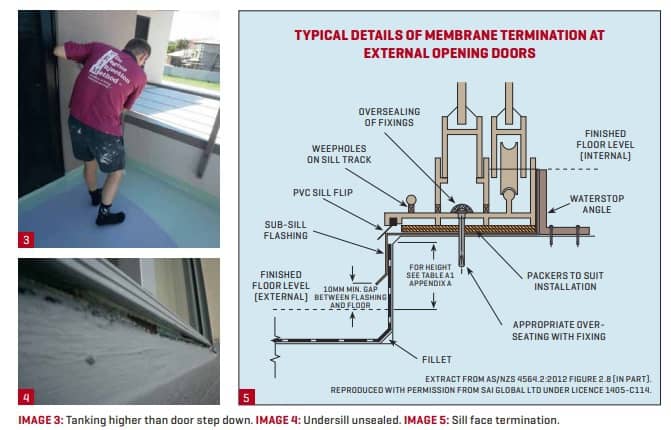

Clause 2.8.3 (a) also prescribes that sub-sill flashing shall be included as part of the membrane system. This has proved problematic during the normal construction process, where previous provisions within the 2009 Australian Standard required full membrane application beneath the door sill. Multiple waterproofing applications, prior to door installation often did not occur (see Image 4).

Where pre-waterproofing did occur, damage to membranes through door installation was often the result.

The current 2012 Australian Standard has been amended to make provisions for detail where the vertical termination of the membrane can be incorporated with a sub-sill flashing. In most cases, this is far more achievable through the normal course of construction processes, but must still be viewed as an integral part of the waterproofing system (see Image 5).

Deck detail includes the treatment of substrate materials, provision of falls, movement joints, penetration details and of course membrane application itself (see Image 6 on page 32).

Decking substrate is to be of a suitable material to withstand exterior conditions over its service life. Particle board timber flooring is NOT suitable under any circumstances. Even if protected from surface moisture, the underside of the timber substrate can be subject to condensation forming through temperature and ambient humidity differences.

This often results in consequential deterioration.

Clause 2.5.2 prescribes a minimum fall requirement for decks to be no less than 1:100. Adequate falls should not just service surface water, but also accommodate sub-tile drainage.

Application of membranes to the top of levelling screeds is a method of managing sub-surface drainage.

This minimises the incidence of cosmetic efflorescence defects and reduces load stresses where, otherwise, the screed would become saturated when the membrane is applied beneath it.

When applied correctly, to a bonded screed, the membrane has falls draining to the lowest point, or outfall. Transference of substrate movement is reduced, as is stress on the floor/ wall junctions.

AS 3958.1-2007 Guide to the installation of ceramic tiles requires a minimum 90% contact coverage of external floor tiles. This not only ensures a positive bond, but also reduces the available cavities for free standing water to lie beneath tiles, hence reducing efflorescence cosmetic defects and stress at the membrane interface (see Image 7).

AS 4654.2 requires detail to edge terminations. Terminations take the form of spitters through parapet walls, drip mould angles into gutters and drip edge angles to deck perimeters.

Spitter pipes should be set with fall and protrude past the external face so as to prevent water rolling back under the spitter and contacting with the wall face. We recommend that spitter pipe diameters be no less than 40mm, to prevent blockage, and that they are designed and placed to cater for rain events as per downpipe calculations (see Image 8).

Drip mould edge angles should be provided at perimeters to ensure that water is directed to drip freely away from fascia linings, and not roll under the angle as per the extended spitters mentioned above. Edge angles should not impede sub-tile drainage.

A number of ready for market edge angles are available, where the angles can be dressed to with membrane allowing for sub-tile drainage through weep holes beneath the tiles (see Image 9).

Drip mould angles to gutters should ensure a minimum of 35mm downturn, into the gutter, with allowance that gutters can be removed without disturbing the waterproofing system.

Final diagnosis

Prevention is far better than cure: it’s a saying that applies to any disease. Following the requirements of the NCC and AS 4654.2 is the bare minimum mandatory prescription.

Therefore, a holistic and sensible approach to design and application is critical. Site specifications from adhesive and membrane manufacturers should be sought and followed, with interim and final inspections. Take these prescriptions, eat your apple now and avoid swallowing the bitter pill when terminal failure comes back to bite you.