When six ain’t six: failing to reach the NCC’s six-star air tightness requirement

Despite the NCC setting a minimum energy rating requirement of six-stars for new homes in Australia, research has found this is routinely not being met due to a focus on ‘as designed’ rather than ‘as built’ performance. Adelle King reports.

Australian Living recently hosted its Educate 1000 workshops in Brisbane, Adelaide, Melbourne and Sydney as part of its national campaign designed to deepen a culture of performance, compliance and collaboration in Australia’s residential building industry. The aim of the seminars was to address the issue of under compliance to state-based energy efficiency and thermal regulations, and drive better communication channels between industry and the community.

According to Australian Living, many new homes and renovations are not meeting building code requirements for energy use and thermal comfort. Yet Australians are increasingly looking for ways to save on energy bills.

According to Choice, homes account for approximately 11% of Australia’s total carbon emissions but the overall energy intensity of residential buildings in Australia improved by only 5% between 2005 and 2015, according to the Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts’ Energy use in the Australian residential sector 1986-2020 report.

Additionally, the International Energy Agency reported that Australia was one of the worst performers in terms of rate of improvement of building energy efficiency between 2000 and 2013.

Aurecon global sustainability leader Jeff Robinson, who presented at the Educate 1000 seminar in Melbourne, says a lack of regulation regarding airtightness after construction is a major reason why Australia is falling behind other countries in the energy efficiency of its residential buildings.

“There has been a lot of progress in terms of increasing energy efficiency and reducing emissions in the commercial sector but this isn’t happening in residential. The mechanisms to check how well a building has been built are fairly limited so there have been cases where there are clear discrepancies between the energy rating listed on paper and the actual energy efficiency of a home.”

Since 2011, all new homes and renovations in Australia must meet a minimum six-star Nationwide House Energy Rating Scheme (NatHERS) or equivalent energy rating. However, a report from engineering and environment consultancy firm Pitt&Sherry, in collaboration with Swinburne University, found the requirements of the six-star NatHERS are routinely not being met. The report, The National Energy Efficient Building Project, found this is due to a focus on ‘as designed’ rather than ‘as built’ performance and a lack of market pressure for energy efficient features.

“There isn’t consistent, rigorous checking and validation processes for energy efficiency measures like air tightness and the installation of insulation during and after construction,” says Jeff.

“This can lead to poorly insulated and leaky buildings, and non-compliance across the building supply chain.”

Unlike in the US and UK, Australia does not require verification of airtightness through testing and inspection, and there is no further assessment after the design stage to ensure recommended energy-saving requirements are installed or installed correctly.

“It is not common practice in Australia to implement mandatory inspections of energy efficiency features and inclusions,” says Jeff.

“There are also some in the building industry who are resistant to change because they fear that it will raise the cost of construction and therefore housing affordability. This needs to change if we are to lift standards in the domestic construction industry.”

While the National Construction Code (NCC) does require residential buildings to include features that minimise air leakage and sets out requirements for common air leakage points to be sealed, it does not specify minimum performance levels that need to be achieved.

The NCC 2019 Public Comment Draft includes some improvements in areas such as split heating and cooling loads, sealing, and condensation management but does not increase the stringency of requirements for household energy performance.

“In the case of residential buildings, in Volume 2 (Residential) of the NCC Public Comment Draft, airtightness testing can be used as a method of demonstrating compliance with V2.6.2.3 verification of building envelope sealing,” says Jeff.

“Compliance with P2.6.1(f) is verified when a building envelope is sealed at an air leakage rate of no more than 10m3/hr.m2 at 50Pa reference pressure when testing in accordance with AS/NZS ISO 9972 Thermal performance of buildings – Determination of air permeability of buildings – Fan pressurisation method.”

Jeff says because the building industry is largely left to self-regulate in regards to the installations of energy-saving measures, even well-built, six-star homes are falling short on airtightness standards.

“Even if a builder does everything right, other trades can come in and cut insulation, affecting airtightness. That’s why we need a multi-layered approach that includes mandatory pressure testing as a requirement of the NCC. Achieving rigorous airtightness is a sign of quality and if a contractor has passed a rigorous, validated airtightness test, the chances are the rest of the building will be of a high standard.”

According to Choice, draught sealing can cut up to 25% off a power bill. Additionally, the Building Code Energy Performance Trajectory Project Interim Report by Climate Works Australasia in conjunction with Australian Sustainable Built Environment Council (ASBEC), found improvements to airtightness could deliver 28%-51% reductions in energy costs. This equates to improvements of up to two and a half stars on the NatHERS scheme.

The Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts says an energy rating improvement of one star can increase the market value of a home by 3% on average.

“Air sealing is one of the most cost-effective and durable interventions that can be made in new buildings under construction,” says Jeff.

“A report by Sustainability Victoria found that even in existing buildings air sealing can have a payback as short as five years and it wouldn’t be expensive to add this as a requirement in the NCC.”

An August 2013 market research study by Sustainability House for the Department of Resources Energy and Tourism found the average cost of undertaking either a thermal imaging assessment or blower door test in a three-bedroom detached single house was $400-$600.

“The average cost of a home in Australia is several hundred thousand dollars so an investment of $800-$1,200 to improve the quality of construction to ensure the home owner gets what they paid for – an energy efficient, well insulated, airtight, comfortable home – represents good value for money,” says Jeff.

“If we got this happening at volume as part of a mandatory requirement of the NCC then it is anticipated that the cost of undertaking these tests will decrease to as little as $300-$500 and a whole industry will start up.”

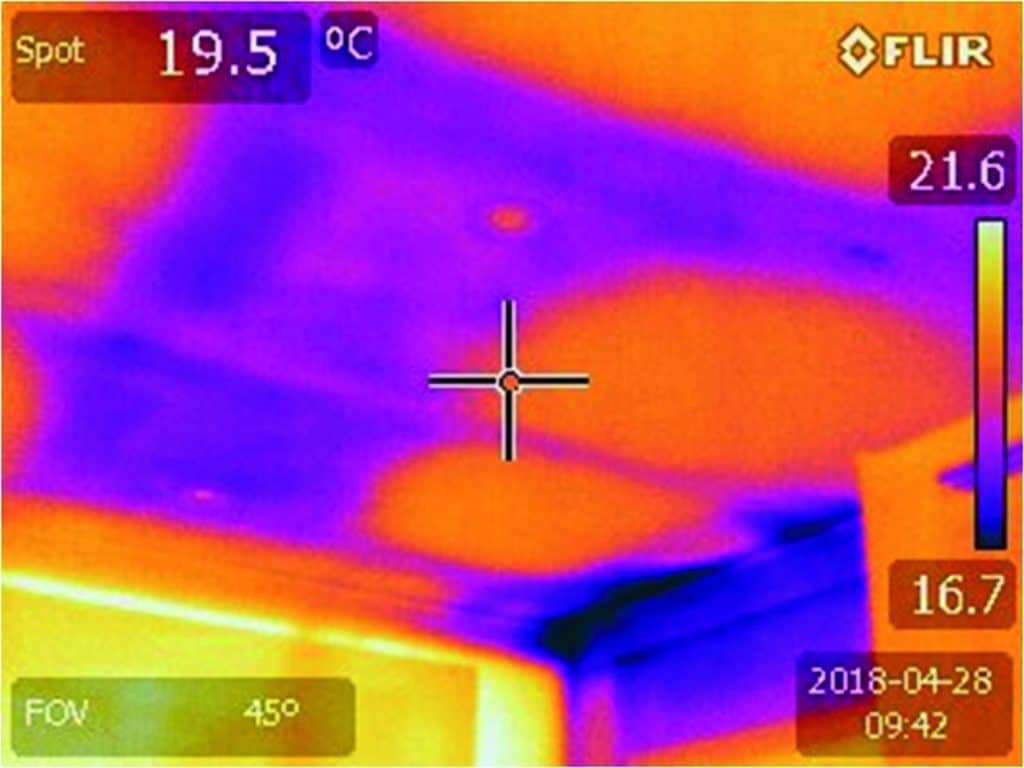

Jeff says he’s advocating for the NCC to include recognition in the form of two certificates for those who are taking care to ensue the energy efficiency of homes they’re building. One would prove that a building has passed an air leakage test, while the other would be a thermographic test to show insulation has been properly fitted.

“One of the challenges with this is that airtightness and insulation aren’t important to most customers because they don’t understand how these work. The responsibility therefore lies with governments to set down the levels required and police methods to make sure these things are being incorporated,” says Jeff.

“However, there are opportunities now for progressive home builders to provide airtightness certificates ahead of regulation in the NCC. In the US, there are 1.6 million energy star homes, saving an average 30% on their energy usage. A similar Australian label would denote buildings that have been inspected for proper air barrier installation and testing compliance with Australian standards.

“A few changes will make a big difference, not only in improving energy efficiency but also the quality of construction.”