Mixed Reality hits the bricks

A Melbourne-based tech startup is shaking up the building and construction industry with its platform for designing and making in mixed reality. Justin Felix reports.

Virtual reality. Augmented reality. Artificial intelligence. Machine learning. They’re all buzzwords doing the rounds in a bunch of industries and the building and construction landscape is no exception. And for early adopters, it’s a seriously exciting time to be in the game, because from here on in, the opportunities and capabilities are only going to broaden.

Fologram, a Melbourne-based tech startup is building the platform for designing and making in ‘mixed reality’. And while mixed reality hasn’t received as much press as the aforementioned buzz words, it’s certainly one to look out for.

In simple terms, mixed reality is a hybrid environment that merges interactive virtual objects with the physical environment. Hence the term ‘mixed’.

Fologram’s software provides designers with a toolkit to create mixed reality experiences within design software they already use, and view and share these experiences through the Fologram app on smart phones or mixed reality headsets.

Fologram’s directors.

“Enabling the design community to extend what they can design and build is fundamental to the work we do. Fologram is for exploring new solutions to the unique challenges facing the architecture, engineering and construction industry in education, research, practice and on building sites,” Fologram co-founder Nick van den Berg says.

“By supporting state of the art mixed reality hardware and making it easier to use, we’ve built a platform to create opportunities for designers to augment all aspects of the design to production process by assisting with drawing, modelling, instructing and making.”

So how does it work?

“Fologram is a software ecosystem that allows mixed reality hardware running our standalone application to talk to desktop design software running the Fologram plugin. Geometry and other model information from your design software is streamed to your headset or mobile phone, and spatial information like device or hand positions are sent back in real time,” Nick explains.

“By using this spatial information to trigger changes in design models, designers can use Fologram to build interactive mixed reality experiences.”

Fologram has been developing an augmented reality platform that extends the skills and capabilities of tradespeople and artisans by allowing them to work with precise digital instructions overlayed directly within their workspace.

And the technology is walking the walk in the field.

“Try showing a bricklayer a design for anything that can’t be built with string lines and plumb bobs and they’ll likely shower you with expletives. And with due cause: the process of measuring, checking and setting out each brick is tedious, time consuming, risky and prohibitively expensive,” Nick says.

“Research institutions and large companies are working with industrial robots to automate these challenging construction tasks. But robots aren’t well suited to unpredictable construction environments, and even the most sophisticated computer vision algorithms cannot match the intuition and skill of a trained bricklayer.”

University of Tasmania (UTAS) invited Colin Barratt and his team from All Brick to try the headset on some of the tricky geometry they were working on at the university. UTAS provided a design model and Colin used Fologram to turn that into a holographic instruction set. That allowed Colin to see the outline and precise placement of every single brick in the wall.

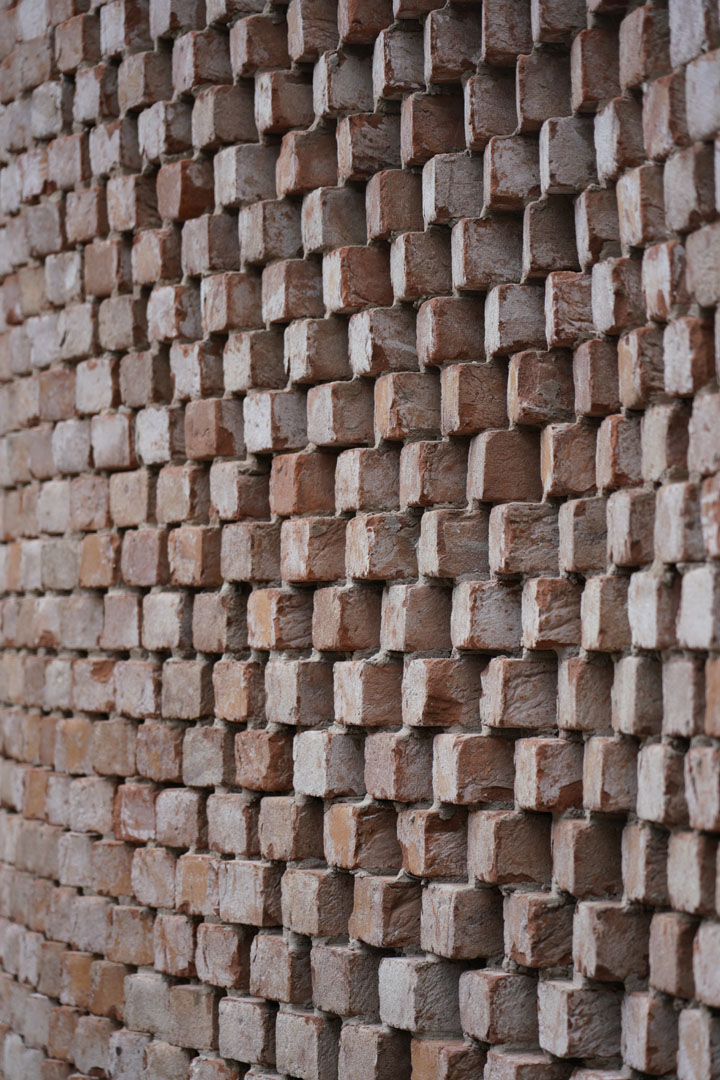

After working with augmented reality instructions to build a curving brick wall in one tenth of normal construction time, Colin and his team at All Brick began referring to themselves as ‘burnt clay artists’.

“There wasn’t a single brick on the wall (see images) that lined up to anything. Every brick was different. That type of job would normally take around two weeks. And a lot of that would be made up as you go. You wouldn’t get it exact. It took two bricklayers 6.5 hours to complete.”

Colin is now confident that he and his team could take on more complex designs and are challenging architects to design for these new capabilities.

“I once saw a program on John Lennon where he explained that after every song he would get scared because he was afraid and thought he should stop because he’d never make anything better.

“And I feel the same after this wall. I want to stop because I’ll never make anything better,” Colin laughs.

With limitless possibilities in the future thanks to this kind of technology, it’s fair to say the building and construction landscape is set to be disrupted in a major way.

“We’re excited by the possibility of working in augmented reality to re-connect the practice of architecture with the craft of building,” Nick says.

By providing designers and makers with clear and contextual descriptions of design intent, augmented reality will gradually eliminate drawings on construction sites and improve the viability of one-off, ambitious, adaptive, sustainable and experimental design.”