Home Warranty Insurance: Wrestling the Beast

State and territory-based home warranty insurance schemes, first introduced in 1972 in NSW, have always been divisive, poorly understood and deeply unpopular with both builders and home owners, writes John Power. However, a new private-sector model – SecureBuild – has the potential to tame the beast while improving industry standards.

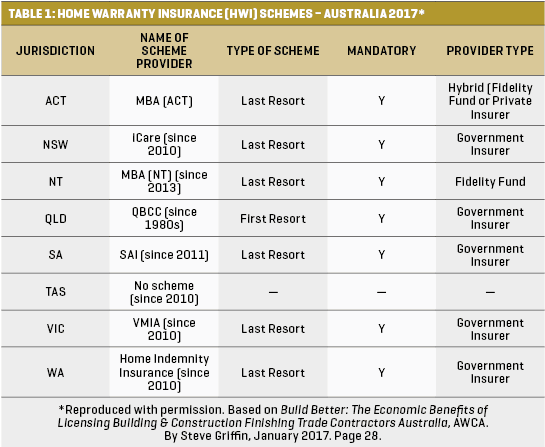

Home warranty insurance (HWI) in Australia has never been formulated at a national level, which is an important ‘first observation’ when assessing the widely disparate models that have evolved separately over the years in all states and territories.

All states and territories administer their own unique, differently named, mandatory schemes (apart from Tasmania, which abandoned its scheme in 2010). See Table 1.

So, what exactly is HWI? In simple terms, HWI is designed to offer protection against defective or incomplete works, to owners of new or renovated dwellings in cases where the builder dies, disappears or becomes insolvent. Variations on the theme are numerous depending on the jurisdiction, but the broad principle of providing a safety net to home owners is consistent. As a rule, the builder takes out the insurance, based on licensing and financial compliance for a given project, and the cost is subsequently borne by the home owner.

The differences between schemes are profound: While most schemes are ‘last resort’ instruments, which means they become relevant once all other channels have been exhausted (including re work undertaken by the builder voluntarily or following a tribunal or court order), Queensland provides a ‘first resort’ scheme, which can be activated even if the builder is an ongoing practitioner. Another important difference relates to the status of the provider. Government insurers deliver most schemes nowadays, but ACT possesses a ‘hybrid’ scheme that relies on a fidelity fund or private insurer.

Over the years, all schemes have undergone substantial structural revisions, oscillating between government and private providers and, arguably, failing to offer stable, properly understood protection to the satisfaction of all parties. To make matters worse, controversies have dogged HWI schemes over the past 20 years and continue to taint the sector with suspicion and derision. Most notoriously, in the period from 1997–2001 when private insurers controlled the sector nationally, the collapse of the insurance company HIH/FAI (which had almost half market share nationally) left builders throughout the nation without cover, severely undermining building activity and leaving many home owners’ projects incomplete or on hold. Similarly, lengthy considerations of claims, sometimes resulting in anxious families being confined to temporary accommodation (even caravans) pending resolution of their claims, have been unwelcome blotches on the HWI landscape.

There are many aspects of HWI that continue to cause resentment:

- Builders resent conditions on schemes that limit the number of building projects that can be undertaken at any given time (typically 4–5 maximum), particularly in the current era when demand for new construction is strong.

- Home owners see HWI schemes as ‘double dipping’. Most reputable builders will happily address and pay for re-work out of their own pocket if a contractor, for instance, makes a genuine mistake. Hence a loading of 5–10% on the cost of a new home to allow for such contingencies. Therefore, HWI premiums represent a ‘second layer’ of protection costs for the home owner.

- Typical HWI premiums on a $500,000 home in 2016 were: $3,590 (NSW), $3,158 (VIC), and $4,560 (QLD).

- Home owners frequently question the value and definition of ‘last resort’ protection. What happens if the costs of intervening ‘first resort’ steps (such as litigation via an administrative tribunal or court) outweigh the value of potential HWI payouts? NB: most schemes have capped payouts (for example $200,000 in NSW; $340,000 in Vic; $150,000 in SA; $85,000 in ACT; $100,000 in WA; and, $200,000 in QLD for defects and $200,000 for no-fault subsidence).

- Home owner claimants may have to wait long periods of time for HWI matters to be finalised. For instance, a vexatious builder who ignores or fails to abide by a tribunal or court hearing might drag out proceedings.

- Government bodies resent the high costs of offering and administering schemes. Contrary to popular belief, HWI schemes are not ‘cash cows’ – providers such as NSW are running at a deficit of 140% per annum.

Steve Griffin, executive director and CEO of SecureBuild, a new company aiming to provide a fresh model of HWI protection (initially in NSW, with other jurisdictions to follow), has vast experience in the HWI market. As a former commissioner of the Queensland Building & Construction Commission (QBCC), deputy commissioner of NSW Fair Trading and assistant commissioner of NSW Home Building Service (NSW Fair Trading), Steve has dealt first-hand with the creation and implementation of HWI policy at the highest levels.

According to Steve, the absence of a coherent national HWI framework is one of the reasons for different schemes’ ongoing problems. Despite attempts as far back as the early 1990s to create a uniform national system, no masterplan has ever gained the sanction of all states and territories.

There was a glimmer of hope in 2008, he notes, with the establishment of a National Licensing Authority… “But it fell in a heap because they tried to implement the wrong license categories, and it was disbanded.”

Steve says the current crop of ‘last resort’ insurance programs arose following the HIH/FAI collapse in 2001, after which other private insurance companies were in no mood to enter the market. Prior to 2001, all schemes were based on ‘first resort’ principles. However, the post-2001 adoption of ‘last resort’ schemes limited to the death, disappearance or insolvency of builders was a practical necessity to restrict the scope of liability faced by providers, and to ‘create market conditions’ that would entice private insurance companies back into the fold. For the same reason, buildings above three storeys were removed from schemes nationally at the same time, as this class of building had been subject to very heavy claims.

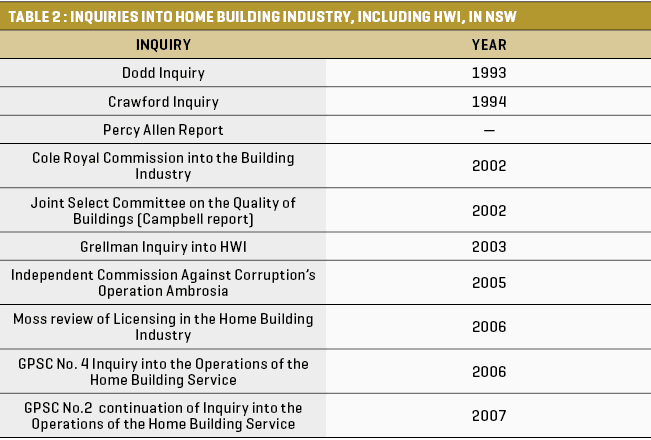

With its sad history of state and territory fragmentation, compromised scope of operations in the wake of the HIH/FAI debacle and persistent image problems, it is no wonder HWI schemes lack dignity or clarity. Successive inquiries over the years into HWI and the broader home building industry (see Table 2 for NSW data) have canvassed different solutions, always treading a fine line between fiscal practicality, fairness to all parties and good functionality, but the result remains a licorice allsorts HWI system spread across eight siloed jurisdictions.

A NEW APPROACH

The abovementioned state of affairs, according to Steve, calls for a radical new approach to the way HWI is formed and implemented.

Steve’s solution has been to come up with SecureBuild, which is a more ‘hands on’ service based on much tighter inspection procedures; greater interaction between the provider, home owner and builder; and better coordinated quality controls throughout the building process. More on this later.

But first, let’s address some financial realities underpinning HWI schemes.

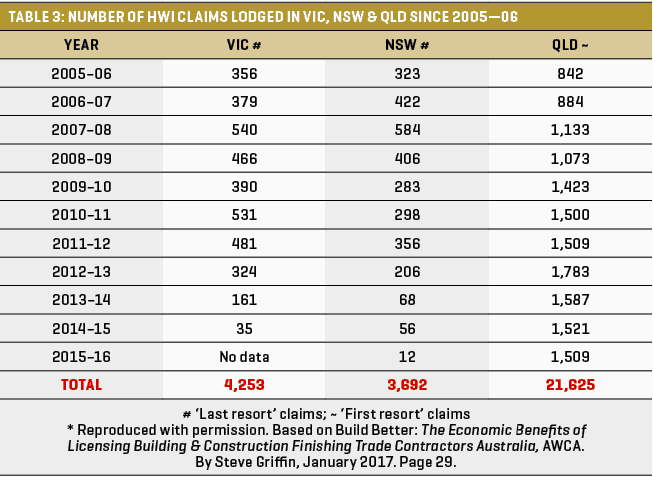

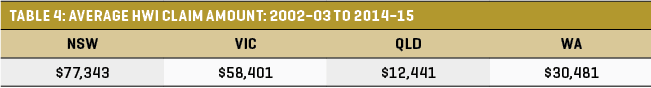

At the most fundamental level, any new HWI model must be fiscally responsible and realistic. A common misconception, Steve says, is that HWI schemes are little more than moneymaking machines – indeed, some new home owners treat HWI protection costs as just another stamp duty or tax. This view is understandable, Steve admits, based on raw memories of the HIH/FAI scandal, as well as what ‘appear’ to be very low numbers of processed claims (see Table 3) and modest average payouts (see Table 4).

In reality, taking into account the fact that most policies have lifespans of approximately six or more years, the majority of schemes are either loss-making or running at a very modest profit. Over the past 20 years, for example, the NSW HWI scheme has run at a loss of 140%, representing a deficit of $40 for every $100 in revenue.

“The [HWI] product covers a six-year period (long tail), so losses on policies issued in any year accumulate over six to even 10 years. That is, a home owner can load a claim under their policy at any time after completion up to six-and-a-half years and it may take another couple of years to complete the claims process,” Steve explains.

“So, to understand the total cost of claims for any one year you have to look back six years. Accordingly, the only claims data that is relevant is data that is more than six years old (‘mature’ data). Look back at the 2007–08 data, which show 585 claims relating to policies issued. This results in a total $45m claims costs. When you subtract commission, admin and agent fees the result is a loss for the underwriter.”

No wonder private insurers have tended to either steer clear of the HWI sector, or accept it grudgingly (perhaps as a lead generator for other more mainstream product lines like home and contents insurance). NB: The revenue pool for HWI schemes nationally is comparatively small – approximately $500m – compared to $3–4bn for compulsory third party (CTP) policies in NSW alone.

FOCUS ON QUALITY, NOT INSOLVENCY

Mindful of these fiscal realities, the first step towards a successful new HWI model (which is both financially realistic AND attractive to builders and home owners) is for the HWI provider to get mud on his hands, Steve says.

If we consider the three ‘risk pillars’ of HWI ‘last resort’ schemes, namely death, disappearance or insolvency of the builder, then it is clear that traditional HWI schemes have focused their efforts on minimising insolvency as a primary means of reducing claims volumes. This fixation on insolvency, Steve suggests, is narrow-minded. Surely a better approach is to focus on improved, higher quality buildings as a means of satisfying home owners and limiting consequent disputes, litigation, tribunal hearings and HWI claims.

While insolvency is common in the building industry, attempts to reduce its incidence by limiting builders to four or five projects at a time is counterproductive, Steve says, and in some cases drives builders to the wall. A more sophisticated approach, he believes, is to recognise that today’s builders are more involved in contract management than ever before, which means today’s contractors and subcontractors have greater autonomy than previous generations and therefore need greater scrutiny. Furthermore, current sign-off processes involving certificate presentations rather than actual inspections, Steve laments, are no substitute for expert examination on site.

SecureBuild, by systematising a minimum of three inspections (or up to 10, by arrangement with the home owner) throughout the building process, increases the odds of small problems being spotted and rectified on site long before they compound into large ones, and while contractors are still around to rectify problems of their own making. This process, in turn, means builders are less likely to be left ‘holding the can’ when it comes to taking responsibility for any major problems at the end of the build, as such matters should have been addressed prior to completion.

As Steve notes, minor mistakes and defects attributable to finishing trades, for instance, represent 12% of all re-work costs in Victoria (9% in NSW). If contractors remedied these kinds of small defects mid-construction under the guidance of professional inspectors, then a large portion of Australia’s total annual re-work bill of $3.3 billion could be avoided, relieving the financial burdens faced by builders and HWI schemes, and easing the minds of home owners.

In summary, Steve says, SecureBuild offers the following benefits:

- Relieves governments of the burden of administering costly HWI schemes and suffering cost blowouts at public expense.

- Offers builders the security of knowing their construction sites are being expertly inspected while contractors are still present to rectify their own mistakes.

- Offers peace of mind to home owners by providing assurance that construction is proceeding to satisfactory standards at every stage.

- Provides significant prestige (and marketing clout) to builders, who are happy to accept and promote independent scrutiny of their work.

WORKING TOGETHER

Of course, the SecureBuild model requires significant cooperation between the home owner, provider and builder to achieve optimal outcomes, but Steve believes a coordinated and transparent approach to construction is the key to efficiency and quality.

Crucially, the collaboration also calls for a more traditional approach to payment schedules, whereby advance payments to builders at various stages of construction would be capped at reasonable levels, say 50% payment up to lock-up stage. Trends towards oversized advances (80–90% or more of the full price to lock-up) have been blamed for home owners getting into unnecessary difficulties in the event of their builder dying, disappearing or becoming insolvent, hence the need for a fairer attitude to payment schedules.

NON-COMPLIANT PRODUCTS

As Steve explains, the SecureBuild HWI model is designed to inspire construction projects that are fair, professional and transparent. An extraordinary side-effect of SecureBuild’s detailed inspection process is an uncompromising approach to non-compliant and non-conforming materials and products.

“If we see a product that’s not compliant and not conforming, we’ll say to all our builders, ‘Don’t use this product from today because we’re not going to cover it and we’re not going to indemnify owners if you use it. And then we will refer it to the government to get it banned.’”

The importance of this stance cannot be overstated, as it represents the first time an Australian insurer has opted to annul claims based on non-compliant product. Who knows: perhaps SecureBuild will accomplish what all state and federal regulators have failed to do so far, and actually spur a meaningful attack against non-compliance.

Overall, Steve says his motives for creating SecureBuild are to restore certainty and value to HWI, and hopefully help reinvigorate the sector.

“In 2008 we had 22,000 builders with cover in NSW at the height of the GFC,” he says.

“Today we have 17,500. So, we have the biggest demand for housing stock in NSW history at a time when we’ve got 5,000 fewer builders.

“People are demanding a better solution because the government insurer is stopping them from building the number of homes we need built.”

SecureBuild’s elegant solutions have been wrought specifically to tame the beast of HWI uncertainty, and its progress will be fascinating to follow. The company aims to commence commercial operations by mid-2018.